‘Schitt’s Creek’ holiday special: For Jews like Johnny Rose, the menorah is still polished and lit, even in diaspora

Celia Rothenberg, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies, was recently featured in the Conversation

Dec 01, 2021

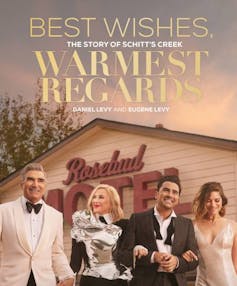

‘Best Wishes, Warmest Regards: The Story of Schitt’s Creek,’ published Oct. 2021.(Black Dog and Leventhal)

The book Best Wishes, Warmest Regards: The Story of Schitt’s Creek by son and father duo Daniel and Eugene Levy, co-creators of the show, was recently published in time for gift-giving this Christmas and, indeed, Hanukkah.

As I have argued, Schitt’s Creek is also fundamentally about Jewish identity and presents one contemporary interpretation of the most central of historically Jewish themes: exile and diaspora. In real life, Eugene Levy is Jewish, as is Johnny. Moira is not Jewish. David names his religious identity as a “delightful half-half situation.”

In the show’s 80-episode run, the Christmas special, “Merry Christmas, Johnny Rose” (Season 4, Episode 13), is among fan favouries. The episode demonstrates how the omnipresence of Christmas has offered American Jews like Johnny a variety of non-exclusive options for handling the holiday season: Ignore or distance themselves from Christmas, embrace (at least) its more secular aspects and bond with other non-Christian groups who may also feel like outsiders.

Johnny’s Christmas tree

Eugene Levy writes in Best Wishes that he hoped the Schitt’s Creek holiday episode would reflect his own real life “manic insanity about the holiday.”

In the holiday episode, Johnny Rose desperately wants a Christmas tree and celebration in his new hometown of Schitt’s Creek. Moira, and grown children, David and Alexis, not so much.

The special shows flashbacks of the lavish, elegant, over-the-top Christmas parties thrown by the Rose family in their pre-Schitt’s Creek life: a towering decorated Norway spruce tree, guests decked out in their fanciest party clothes, champagne flowing freely and, in the background, panned over very quickly by the camera, a silver menorah, just slightly behind and to the side of the tree.

‘Schitt’s Creek’ Holiday Special, ‘Merry Christmas, Johnny Rose’ CBC comedy video.

Jews and Christmas

Just how representative of American Jewry’s relationship to Christmas is Johnny’s love of the holiday?

Orthodox Jews are, unsurpisingly, the least involved in even highly secularized Christmas celebrations. Indeed, it might surprise some observers to know that even one per cent of ultra-Orthodox Jews reported to the 2013 Pew survey that they placed Christmas trees in their homes.

Many Orthodox Jews today abstain from Torah study on Christmas eve.

Daily Torah study is believed to be a religious obligation. So why abstain on Christmas Eve? The fraught and often dangerous historical relationship between Eastern European Orthodox Jewry and their Christian neighbours shaped the religious practices of these Jewish communities on Christmas. By the early 17th century, many Hasidic Jews followed the practice of not studying Torah on Nittel Nacht (Nativity night), or, as it is called today, Christmas Eve.

Explanations for the prohibition on Torah study include the practical: there was an increased risk of violence against Jews on Christmas Eve, so Jews should not risk travelling to their houses of study. Other explanations focus on the the more mystical, such as the belief that Jesus is being punished for his sin of apostasy, and that the spiritual benefits of Torah study would bring him respite.

Jewish composers of Christmas songs

American composer Irving Berlin, a Jew, wrote ‘White Christmas.’

Liberal American Jews, on the other hand, have a long history of not only celebrating, but also helping to create Christmas traditions. The iconic Christmas songs “White Christmas,” “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree,” “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” “Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow,” “Silver Bells,” “The Christmas Song” and “Walkin’ In a Winter Wonderland” were all written by Jews.

These Jewish songwriters, children of Jewish immigrants, found the Christmas season to be an opportunity to showcase their talents. Composing Christmas music helped them to enter into the worlds of Broadway and Hollywood while demonstrating their wholehearted embrace of their new homeland.

Some American Jews also enjoy Christmas decor, particularly the Christmas tree, during the holiday season: The Pew 2013 report found that nearly a third of Jews report having a Christmas tree in their home. Many liberal Jews in the late 19th century decorated their homes with trees, including famous Jews like U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jew appointed to the Supreme Court.

The practice declined somewhat mid-century, only to increase once again in the past 40 years in parallel with increasing rates of intermarriage and the arrival of many Russian Jewish immigrants who were accustomed to celebrating the season with a “New Year’s tree.”

Syncretic religion?

Are Jews who delight in their Christmas trees embracing a syncretic form of religion — a fusion of different religions’ beliefs and practices — or signalling their participation in groups such as Jews for Jesus? Overwhelmingly, no.

Going out for Chinese food on Christmas: A Jewish tradition. (Shutterstock)

Rather, Christmas is embraced by many liberal Jews as a secular American holiday, described by Rabbi Lawrence Hoffman, a liberal Reform rabbi, as a holiday when Americans are “infused with good will toward all.”

For Rabbi Hoffman, however, the essence of Christmas remains “a feast on the Christian calendar celebrating the incarnation of the son of God.” While Rabbi Hoffman writes that he likes Santa, Christmas music, his neighbours’ wreaths and Christmas trees, he draws the line at celebrating even a secularized version of Christmas in his own home.

Whether Jews put up Christmas trees in their homes or not, however, there is one practice often shared across the spectrum of Jewish movements today: Eating Chinese food on Christmas.

At her confirmation hearing in 2010, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan was asked by U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham where she had spent the previous Christmas. Justice Kagan famously replied, “You know, like all Jews, I was probably at a Chinese restaurant.”

Menorah travelled with them

At the end of the Schitt’s Creek holiday special, Johnny spots his menorah, all eight candles lit, and moves it away from the garland hanging over it, for fear it may cause a fire and burn down the motel.

Johnny’s motel menorah. (Schitt's Creek/CBC)

The menorah, unlike so many other trappings of the Rose family’s life pre-Schitt’s Creek, travelled with them.

Neither forgotten nor left behind in the chaos of their exodus, the menorah is still with them, polished and lit: a miracle, indeed.

Celia E. Rothenberg, Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.